Antelopes are among Earth’s most fascinating animals, showcasing elegance and speed. Predominantly inhabited in Africa and parts of Asia, these sleek grazers exhibit a remarkable diversity of shapes, sizes, and colours.

India is home to a fascinating diversity of antelopes. There are 6 species of antelopes found in India. These are Tibetan Antelope (Pantholops hodgsoni), Tibetan Gazelle (Procapra picticaudata), Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus), Four-horned Antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis), and Chinkara (Gazella bennettii).

From the rugged, cold deserts of the Trans-Himalayas to the rolling plains and forests of Peninsular India, six unique species thrive across varying landscapes. These antelopes represent not only the rich biodiversity of India but also the delicate balance between wildlife and their rapidly changing environments. The six species of antelopes are:

There are 6 sPECIES OF ANTELOPES IN INDIA

1. Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus)

IUCN Status – Least Concern

The largest antelope in Asia, native to the Indian subcontinent. Nilgai are huge creatures, equivalent in size to horses; males are blue-greyish in hue, while females are brown. Both males and females have two white dots on their cheeks on either side. They breed from December to March but can mate all year round.

Nilgai are highly adaptable, capable of surviving in drought-prone areas. They are found from the Himalayan foothills through western and central India to the Odisha coast and south to the Nilgiris.

Also know about: Indian Giant Squirrels

2. Indian Gazelle (Gazella bennettii)

IUCN Status – Least Concern

This species, sometimes known as Chinkara, is distinguished by its tawny brown colour and very slender horns, with the exception of males, who have ringed horns. It is adapted to long periods without drinking, obtaining moisture from its forage.

They are polygamous and fiercely territorial. Chinkaras can mate twice a year from August to October and March to April. They are found from Punjab and Rajasthan, through the Gangetic Valley, and south to the Deccan Plateau.

3. Four-Horned Antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis)

IUCN Status – Vulnerable

The smallest bovid in Asia, native to the Indian subcontinent. The males and females are both light brown and they are the only antelope with two pairs of horns, the front pair being shorter.

It is often found near water bodies and can be aggressive, especially during mating season which occurs during the monsoon from July to September. Its distribution includes the Sub-Himalayan Terai, central and peninsular India, north of the Nilgiris, and Gir National Park.

Also know about: Black Panther in India

4. Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra)

IUCN Status – Least Concern

Known for the sexual dimorphism in colouration, with males having rich, dark brown sides and females being yellowish. Males have distinctive divergent horns and a more robust build. The females are smaller in size as compared to the males. Blackbucks are polygamous and social, known for their lek-mating behavior.

They can mate twice in a year from August to October and March to April. Breed twice a year from February to March and July to August. Their range extends from Rajasthan to Punjab, down to Tamil Nadu, and across to Odisha.

Also know about: Species of Cheetah

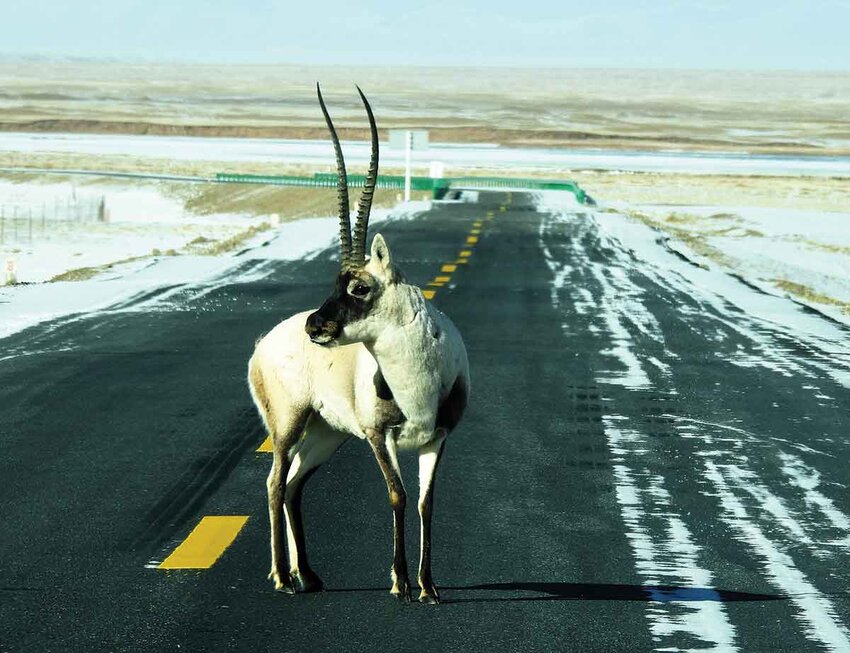

5. Tibetan Antelope (Pantholops hodgsoni)

IUCN Status – Near Threatened

Also called Chiru, this species is found in flat to rolling terrain at elevations of 4000-5000 meters. It has adapted to extremely cold temperatures surviving in temperatures as low as -40°C with a thick, woolly coat and the underfur which is one of the lightest and warmest in the world.

They migrate for food and mating, females stay together in groups for calving, while males live solitarily, reuniting only for mating. The mating season lasts from November to December. They are found in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Tibet.

6. Tibetan Gazelle (Procapra picticaudata)

IUCN Status – Near Threatened

Endemic to the Tibetan Plateau, sandy brown in color, males of these species have long ridged horns. These gazelles live in high-altitude dry grasslands and steppes between 3950 and 5500 meters. Like the Tibetan antelope, they have adapted to high altitudes with thick fur and genetic traits suited for harsh environments.

The rutting season is from January to February. They are found in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Northern Sikkim.

Where do Antelopes exist in animal kingdom?

Antelopes belong to the order Artiodactyla within the Bovidae family. Bovids are ruminants with a complex digestive system, typically consisting of four chambers. They initially swallow their food, which then moves to the first chamber where it is broken down into cud, regurgitated, and chewed again before passing through the remaining chambers for further digestion.

During human evolution, domestication of various species of mammals including bovids like cattle, goats, and sheep is well evident majorly for their extreme agility, ease of taming and their marvelous physical endurance.

Physical and Social Adaptions of Antelopes

Many antelopes inhabit arid regions and have adapted to survive in such environments. For instance, during the hottest months, they shift their foraging habits to morning and evening. When water is scarce, they consume leaves from plants with water-storage organs, such as roots and succulent stems.

Some African species, like the addax (Addax nasomaculatus), can go for extended periods without drinking water, deriving hydration from their plant-based diet. Similarly, the springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) survives years without direct water intake by obtaining moisture from its food and having highly efficient kidneys.

Antelopes demonstrate social behaviour in which they gather in large herds to provide protection from predators; they have both species that normally live in herds, as well as those that prefer to be solitary.

Many antelopes, such as the nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) and four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis), have latrine sites where they excrete on a regular basis as a way of communication to mark territories or leave their smell, and during mating season, certain antelope males flaunt their horns to impress females.

Global antelopes Diversity

Antelopes are a diverse group with around 91 species spread across Africa and Asia. Africa hosts the majority of these species, while only 14 species are found in Asia. Ranging from the smallest antelope in the world royal antelope (Neotragus pygmaeus) weighing up to 2 kg to the largest in the world the giant eland (Taurotragus derbianus) weighing up to 800 kg.

India’s unique and diverse geographical location—bordered by the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean—makes it a biodiversity hotspot. From the high-altitude of the Himalayas to the lowlands of the Ganges-Brahmaputra, India is home to a wealth of animal and plant species.

In India, antelopes inhabit a diverse range of environments, from the high-altitude of the Trans- Himalayan cold deserts to the semi-arid regions of central India, including the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, and extending southward to the Nilgiris. This adaptability demonstrates their ability to thrive in various terrains, where vegetation can range from sparse to plentiful.

Differences Between Antelopes and Deers

| Antelopes | Deer |

| Belong to the Bovidae family. | Belong to the Cervidae family. |

| Have permanent horns. | Shed antlers annually. |

| Both sexes of antelopes have horns. | Usually in deer, only males have antlers. |

| Larger in size to deer. | Smaller in size as compared to antelopes. |

Importance of Antelopes

Antelopes play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of ecosystems. As primary consumers, they not only benefit their habitat but also support apex predators at the top of the food web. They regulate vegetation growth and weed proliferation, which helps prevent wildfires and creates a balanced environment.

They serve as essential food sources for carnivores, supporting the upper trophic levels of the food web. Their fecal pellets serve as natural soil fertilizer and help in increasing ecosystem productivity.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

1. Hunting

Antelopes are hunted for their meat and underfur. Tibetan antelopes, for example, have been specifically targeted for their underfur, which is used to make “shahtoosh” shawls. The extent of poaching has been severe, leading to a dramatic decline in their population from around a million to just 50,000 (source: WTI; news and updates).

Despite a ban on this trade, illegal trafficking persists. Similarly, Blackbucks in India continue to be poached for their skin.

2. Diseases

In India, antelopes are susceptible to diseases such as foot and mouth disease, rinderpest, and other infections (Menon Vivek; Indian mammals;2023)

3. Competition

Competition with domestic livestock is another reason for the decline in these species as seasonal livestock grazing practices is quite common in high mountains.

4. Climate Change

These animals struggle to survive as a result of the Climate changes brought on by global warming; even if they may have adapted to drink less water, dehydration can still be fatal due to the unnaturally rising temperatures.

Even though Tibetan antelopes and gazelles are resistant to low temperatures, they can nevertheless succumb to these extreme conditions. On the other hand, habitat destruction, fragmentation and other climate change-related impacts cannot be neglected.

Ecotourism and the Role of Antelopes in India Wildlife Safaris

Antelopes are not only essential to maintaining India’s ecological balance but also play a significant role in the country’s booming ecotourism sector. Many wildlife enthusiasts from around the world visit India to witness the diversity of its fauna, including species like the nilgai, blackbuck, and chinkara, which are frequently spotted during India wildlife safaris.

National parks such as Ranthambore, Gir, and Kanha offer visitors a chance to see these graceful species in their natural habitat, making antelopes a highlight of many wildlife safari tours in India.

Conservation efforts and remarkable examples

Natural Resources Conservation Outside Protected Areas (NRCOPA) scheme in Ganjam district, which supports projects like the Bhetonai-Balipadar project to protect Blackbucks. As well as the Ranibennur Blackbuck Sanctuary; a protected area for the blackbuck population.

The Indian government has banned shahtoosh shawls and designated the Chiru as a protected species under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972. This legislation ensures that antelopes in India receive the same level of protection as tigers.

Awareness campaigns, especially in rural areas surrounding forests, are crucial. As some of the tribes still rely on meat of deer and antelopes for food. Hence it is important to carry out such programs. These efforts help people understand the importance of each species and the impact of their extinction on the ecosystem. Getting involved with local wildlife rescuers or visiting national parks and sanctuaries can increase awareness and support conservation.

India promotes ecotourism, and as this sector expands, local awareness increases, fostering community involvement in conservation efforts through ecotourism.

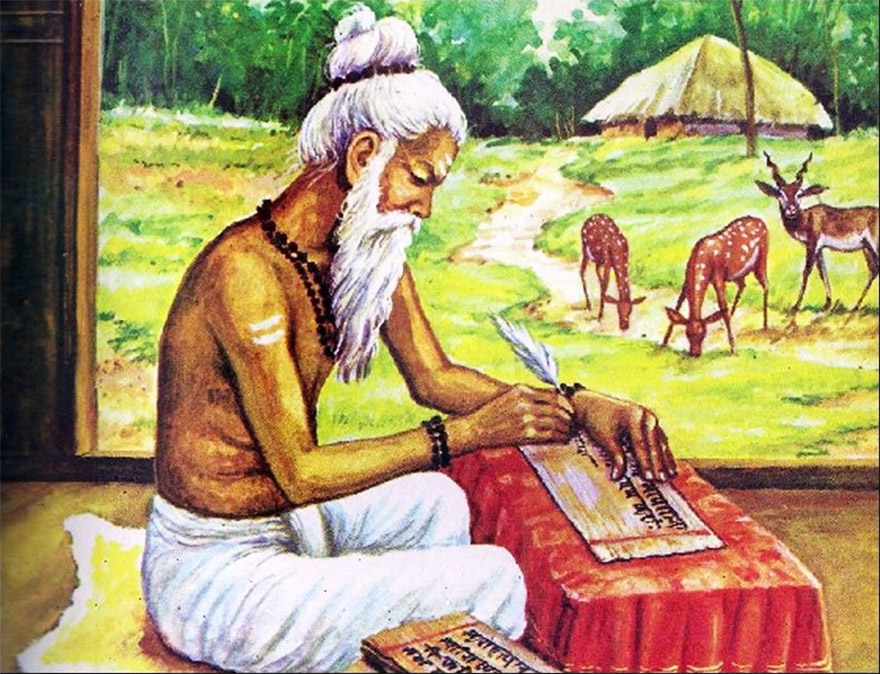

Cultural Significance

Antelopes and deer have been depicted in Indian art and texts since the Stone Age. Ancient Indian texts, such as the Purushacharanavah, Aitareya Brahmana and Ramayana, highlight their elegance, beauty, and grace. The Yogini Temple of Hirapur features a blackbuck sculpture, and it is believed that gods like Vayu and Chandra embody qualities of antelopes. These depictions reflect the deep cultural connection between humans and wildlife.

As we continue to impact our environment, it is vital to ensure future generations can enjoy the rich wildlife we have today. Simple actions, such as reducing plastic waste, as plastic bottles can take up to 450 years to decompose, So such steps can contribute to a healthier planet and sustainable framework.

If you’re passionate about India’s wildlife and want to experience the thrill of seeing antelopes up close, explore our exclusive India wildlife safaris with Pugdundee Safaris, where you’ll be guided by expert naturalists.

Written by Divyajit Kaur Bal, Trainee Naturalist at Pugdundee Safaris

Further reading/references

-

- Arandhara, S., Sathishkumar, S., Gupta, S., & Baskaran, N. (2023). Population demography of the Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra (Cetartiodactyla: Bovidae) at Point Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 15(8), 23641-23652.

-

- Bari, M. N. (2023). Representations of Antelopes and Deers in Early Indian Art and Literature. Retrospect, 111.

-

- Blank, D., & Li, Y. (2022). Antelope adaptations to counteract overheating and water deficit in arid environments. Journal of Arid Land, 14(10), 1069-1085.

-

- Carter, A. M. (2019). Evolution of placentation in cattle and antelopes. Animal Reproduction, 16(1), 3.

-

- Dookia, S., & Goyal, S. P. (2007). Chinkara or Indian Gazelle. In “Ungulates of Peninsular India.” ENVIS Bulletin, Wildlife Institute of India, 103-114.

-

- Menon, V. (2023). Indian mammals: a field guide. Hachette India.

-

- Prasad, S. (2022). High Time of Pacing Nilgai Antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus) into Mainstream as Community Conservation for Influencing Macroeconomics. Asian Journal of Research in Zoology, 5, 21-30.

-

- Pringle, R. M., Abraham, J. O., Anderson, T. M., Coverdale, T. C., Davies, A. B., Dutton, C. L., Gaylard, A., Goheen, J. R., Holdo, R. M., Hutchinson, M. C., Kimuyu, D. M., Long, R. A., Subalusky, A. L., & Veldhuis, M. P. (2023). Impacts of large herbivores on terrestrial ecosystems. Current Biology: CB, 33(11), R584–R610.

-

- Schaller, G. B., Junrang, R., & Mingjiang, Q. (1991). Observations on the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsoni). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 29(1-4), 361-378.

-

- Schmitz, O. J. (2008). Herbivory from individuals to ecosystems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 39(1), 133-152.

-

- Shawl, T., Tashi, P., & Panchaksharam, Y. (2008). Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh (Vol. 60). New Delhi, India: WWF-India.

-

- Swamy, K., Karthikeyan, M., & Boominathan, D. (2020). Habitat preference and biotic pressure of four horned antelope in Sathyamangalam wildlife sanctuary, Tamil Nadu, southern India. International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies, 7, 109-114.